Improving Hiker-Load Relationship

This post has been divided into two sections and is a continuation of the three-part series on why you should start taking greater consideration to the loads a hiker brings out with them while hiking, backpacking, and camping with thoughts on decreasing load weight.

Part 1 – Effects of Load Weight on a Hiker

Part 2.1 – Methods to Decrease Load Weight While Backpacking / Camping

Part 2.2 – Methods to Decrease Load Weight While Backpacking / Camping

Part 3 – Improving Hiker-Load Relationship

Welcome to our recurring series of “The Path Less Traveled.” In this series, we want to take you along for our exploits out in the wilderness while hiking, camping, exploring, and general adventuring. This will include our small daily victories, foibles, tips, tricks, and reviews of gear we authentically appreciate and frequently utilize. While a well-worn trail can often be the pathway to a leisurely day, the paths less traveled can often spur on some of the greatest memories, misadventures, and fun we could imagine. Join us in the Comments as we share our travels, and hopefully, we can all come together for a greater appreciation of the outdoors.

On Last Week’s Episode

In the past two portions of this trilogy, we have learned that weight can cause injuries, decreased endurance, increased caloric expenditure, and lower overall speed. We have also reviewed places and ways we can reduce the weight of our backpacking load-out; unfortunately, this either means getting rid of things or spending more money.

Ways to Improve Hiker-Load Relationship

When lugging weight around – either marching, hiking out in the woods, or working at WalMart and stocking shelves, there are things we can learn to improve our relationship with that weight. Does the backpack/load-out fit well? Once having a pack, how much weight should one carry, and how is this determined? (Is BMI a reliable measurement tool?) Are there ways to adjust what/where you are carrying your load-out to improve mobility, speed, and endurance? YES.

Lastly, we have to consider the most invariable element of the hiker-load relationship – the hiker. There are ways we can improve the hiker to adapt to the load-out, and consider accommodations to reduce chances of mobility inefficiencies and/or injuries.

Improving Hiker-Load Relationship – Fit

Biologically, men and women have different body features that should be accommodated in order to ensure that a backpack fits the wearer ideally; otherwise, a pack can flop/sway/bounce around that can increase discomfort/injuries and inefficiencies. David Boulware, M.D. even determined separate packs for men and women are more than beneficial – it is vital.

“The testers in that study used backpacks with no differences for females. However, in another study where women used their own packs fitted for them, the percentages of injuries were not significantly different from that of men (Boulware, 2004).”

If you’re looking online for a new bag, size up your torso before deciding. REI has a great video for this:

(TLDW: Measure between Iliac Crest and C7 Vertebrae. This length is separate from your overall height. The important factors are that the hip-straps will land 1″ above the hips when un/lightly-loaded, and that the shoulder strap should roughly start on the pack 2-3″ below the top of your shoulder, that way the curve of the strap can allow adjustment.)

Backpacks not fitted well can result in injuries to the lower back; these injuries can further shift to other parts of the body causing them to overcompensate and result in additional injuries.

Improving Hiker-Load Relationship – Weight

We’ve all read that we shouldn’t be regularly lifting more than X amount of weight, or X% of our Total Body Weight. The typical number is 30%; heck that is what MIL-STD-1472F 5.11.1.2.2 claims:

“5.11.1.2.2 Load carrying. The total load carried by an individual, including clothing, weapons, and equipment for close combat operations, should not exceed 30% of body weight… …personnel with 5th percentile body weight must be accommodated, the total load for close combat operations should not exceed 18.5 kg (41 lb) and, for marching, 27.7 kg (61lb).”

Is 30% really a sensible weight? My typical weekend load-out is 5.15kg (11.35 Lbs), and overnight is 2,852g (6.29 Lbs). Overall, I rarely carry more than 9kg (20 Lbs). I couldn’t imagine carrying 19kg (43 Lbs) [145lb body weight].

So, I recommend this – Strip naked, get on your scale, and weigh yourself; write this down. We all know what level of fitness we’re at. Let’s now disregard our actual weight and look at our ideal weight.

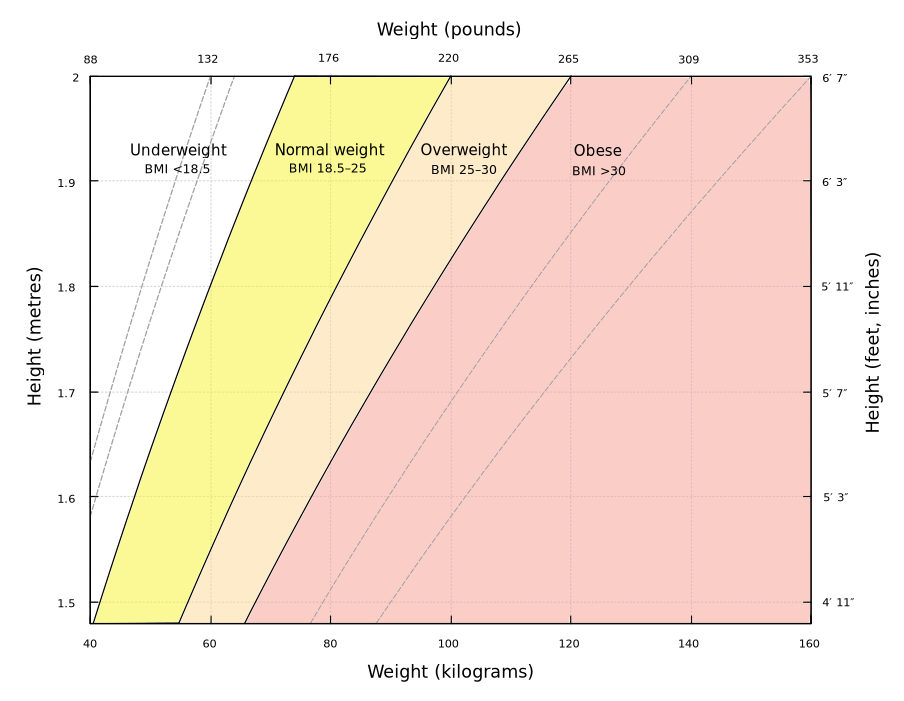

Everyone knows BMI, but for the past 30-40yr, it has been criticized for its inaccuracy for muscular and stocky individuals. I’m sure you’ve heard that one guy in the Navy complaining he was told to lose weight because of how thick his neck was or something like that.

From now on – use Relative Fat Mass when evaluating yourself instead of BMI (Ultimately, BMI is much easier to do this calculation with). Find your perfect weight in the BMI “Normal” range (18.5%). Use this number as your relative pack weight ratio threshold. For me, that’s 118lb, despite weighing 145lb.

Now, let’s really go down to your pack being 10-12% of your ideal body weight when doing a 1-3 day hike (12-20% for 7+ Days). For me, this would mean 5.35-6.42kg (11.8-14.2lb)

How does this compare to your backpack’s current weight?

Improving Hiker-Load Relationship – Distribution of Pack Weight

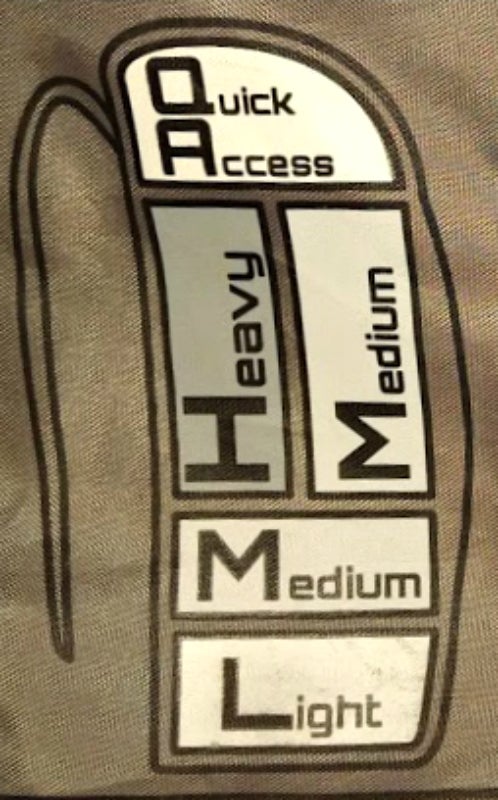

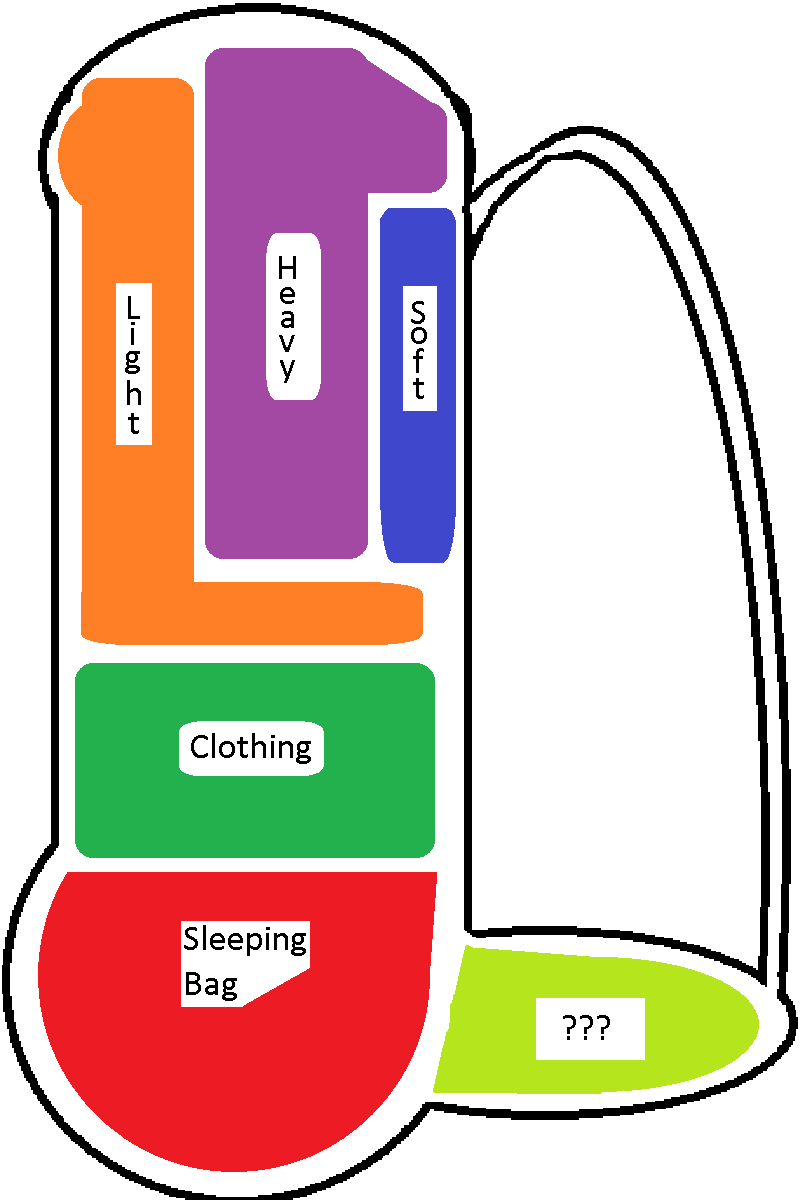

Distributing your weight in the pack closest to your body is the best way to keep the load from causing a pendulum effect. Having the weight away from the bottom can also prevent the weight from slapping against the bottom of your hips/spine. There are two methods of thought for this. One, I found in my very first bag; it seems to work best not only for hiking on flat land, but also for steep climbing, as less focus is put on weight higher up.

The traditional pack weight distribution looks more like this:

I’m hoping that your analysis of these two methods helps you understand not to place your bear canister, water bottles and/or cooking system on the back end of your pack. There are also studies indicating a “bodypack” can increase one’s endurance/stamina…. but I don’t think we’re culturally ready to have backpacks with a frontal load-bearing section, yet.

Improving Hiker-Load Relationship – Factors That Affect Hiking/Backpacking

Everyone’s body is different. Be sure to take this into consideration when carrying weight.

NONE OF THIS IS TO BE CONSIDERED MEDICAL ADVICE

Bad knees? Try trekking poles. Trekking poles reduce the load on the knees every step and increase balance. This helps distribute load while increasing the number of repetitions they can endure. Bone pain from worn-out joints? Readjust where the weight is loaded – once again, try the front-pack kangaroo packs.

If age or bodyweight are hindrances, I’d recommend increasing your training and endurance through exercise. Exercise is the best and easiest way for an individual to be able to adjust to the pack-weight they carry.

I cannot give enough time and words for increasing your training and pre-hiking exercise, but so many others explain it so much better. If you have any other recommendations – leave a comment below!

The post The Path Less Traveled #009 – Improving Hiker-Load Relationship appeared first on AllOutdoor.com.