Imagine a group of children playing outside, clambering up and down whatever happens to be available, be it trees, rocks, climbing frames, buildings, freakishly tall adults. Pretty soon and without giving it much thought, they’re going to notice it’s easier to reach the top of some obstacles, whereas others take more effort. This tree is harder than that one; that rock is easy on this side, but more challenging on the other. And, by ranking their difficulty, they are in essence giving them a relative grade, although there has been no talk of numbers or systems.

But once adults start playing children’s games, things change! Adults, especially competitive ones, like to impose order on random play. They like there to be a structure, a clear way of measuring difficulty, as well as a strong desire to know who’s the best.

In a roundabout sort of way, that explains the birth of bouldering grades – read on to learn more!

- What are bouldering grades?

- Why grade?

- How are bouldering problems graded?

- Different grading systems for bouldering

- Bouldering grades conversion chart

- Fontainebleau bouldering grades

- V scale bouldering grades

- Hybrid bouldering grades

What are bouldering grades?

Bouldering grades, and climbing grades in general, are systems of numbers (or numbers with letters and symbols) that convey the degree of difficulty. Its nuances can be quite complicated for the beginner to understand, especially because there is not one universal system.

But having said that, the different systems share a simple rule in common: the higher the number, the harder the climb. Another useful rule is that grades make more sense when viewed as a relative scale. Rather than thinking about any absolute qualities that are necessary for a problem to be graded a V5, for example, it’s more helpful just to know that it should be harder than a V4 and easier than a V6.

Why grade?

As suggested in the introduction, the wish to rank seems innate, and for an activity to move from play to a recognised sport, it’s invariably accompanied with greater rules and structure. Most significantly, grading allows you to know the difficulty of the boulder problem before you attempt it. And when compared to the maximum grade you’re capable of climbing, you will know whether you should find it easy, a challenge, or too hard in your current state of fitness. Another reason to grade is that it gives you a great feeling of progression and achievement when you climb a problem graded harder than anything you’ve done before.

How are bouldering problems graded?

Who decides that the pink holds in the far corner of your local indoor wall constitute a V2? The answer is the route setter, the person who put those sized holds in that particular configuration. But you might now be asking, how does she know the pink holds are not a V3? It’s all about experience, of having climbed numerous other comparable problems, and therefore being able to ‘feel’ that the pink problem is too easy to be a V3, but too hard to be V1. You’d be right in thinking that it’s not the most scientific approach, but the greater the experience of the route setter the greater the accuracy. Plus, if subsequent climbers think the problem’s been over or under-graded, then it can change.

For outdoor bouldering grades, instead of the route setter, it’s the first person to climb to the top of that particular rock. Experience again enables the first ascensionist to compare the new problem to others she’s climbed, thereby determining what grade to give it. Consensus of opinion is also more prevalent outdoors as the problem won’t change, enabling more people to climb it.

Different grading systems for bouldering

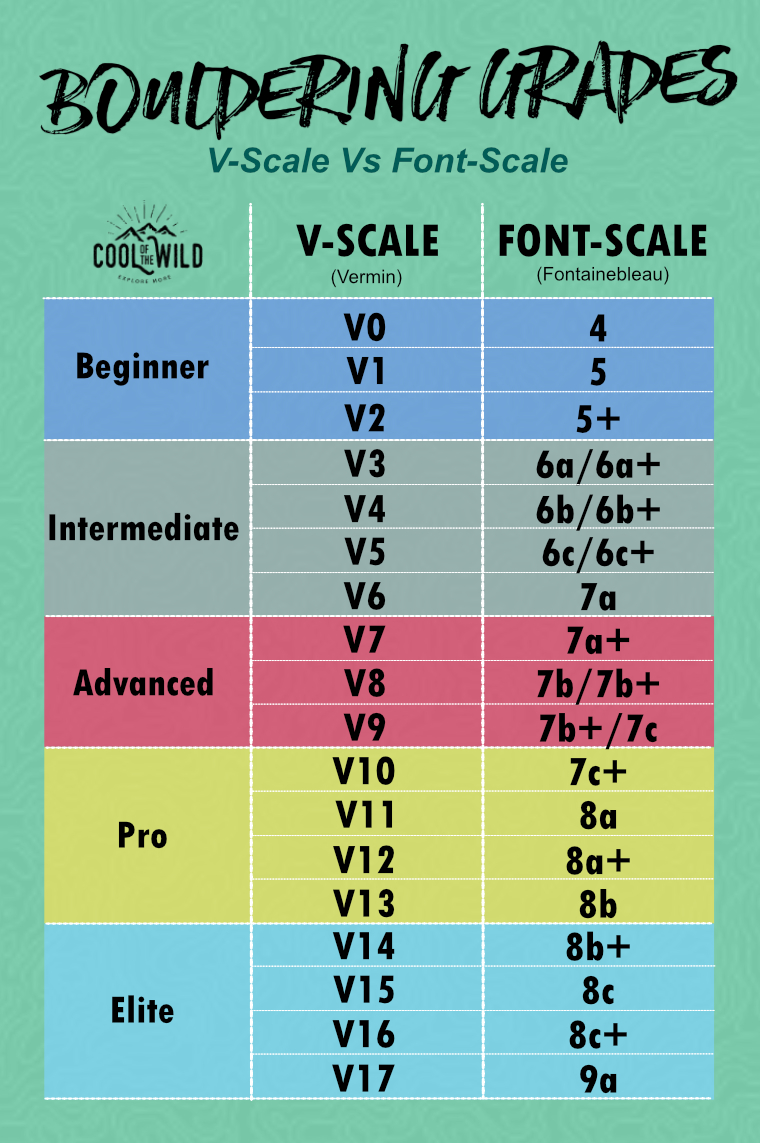

It would be much easier if only one bouldering grading system existed, and only one system of climbing grades too. Sadly, there are quite a few out there to confuse you. But to make our life easier, you only really need to learn the two most popular: the Fontainebleau system, abbreviated to Font or ‘f’, and the V system. Bouldering conversion charts show you how the systems compare to one another.

Bouldering grades conversion chart

01Fontainebleau bouldering grades

The Font system is named after France’s most famous bouldering destination, the wonderful sandstone boulders in the Fontainebleau forest. It is where bouldering originated as a climbing discipline distinct from merely practising for traditional and alpine routes, and that legacy is reflected in the popularity of the Font system.

The grading begins at f1, though the easiest grade in most indoor and outdoor venues is f3. The grades are also subdivided by adding a ‘+’ to the number, and ‘a’, ‘b’ or ‘c’ at f6 and above, with ‘a’ being the easiest subdivision and ‘c’ the hardest. The Font scale is open-ended at the top end, but the world’s hardest boulder problems are currently f9a – see below for news of a recent repeat of the world’s first 9a by a fiendishly strong Scottish climber.

Pros of Fontainebleau bouldering grades:

The system is especially sensitive around the mid-level, about 6a to 7a, with more distinct grades for the same range of difficulty in comparison to the V system. For example, the three V grades of V2, V3 & V4 are covered by f6a, f6a+, f6b and f6b+.

Cons of Fontainebleau bouldering grades:

The main disadvantage of the Font system is that it’s confusingly similar to the French sport grading system, with comparable numbers and letters and pluses, as well as some similarity to UK trad technical grading. It shouldn’t be too much of an issue as sport grades would never be given to boulder problems. But do be aware that while the numbers and letters look the same, they do not indicate the same level of difficulty. For example, if you’re a 6a sport climber, you might not have the strength or skill to boulder Font 6a.

02V scale bouldering grades

Younger than the Font system, the V scale was developed in the 1980s by the American bouldering pioneer, John Sherman (nicknamed ‘Verm’ – hence the ‘V’).

The majority of the grades simply consist of a ‘V’ followed by a number, with no additional letters or symbols; these run from V1 to V17, which is currently the highest grade, and equivalent to f9a. Like the Font system, it is open-ended. The V scale includes a few extra symbols for grades below V1. Starting from the easiest, they are: VB, V0-, V0, V0+.

Pros of V scale bouldering grades:

It is the simplest system without multiple letters and covering a range of numbers more distinct from other route grades. It is especially clear and less cluttered at the top end, V9 and above, so in that respect, it’s more targeted towards strong boulderers.

Cons of V scale bouldering grades:

The V-system is less sensitive at the lower and mid grades, with one grade covering the same degree of difficulty as one and a half to two Font grades. A boulderer of V1 ability, for example, will notice a greater spread in that one grade, with some feeling a lot harder than others; she might therefore find the font system more helpful.

03Hybrid bouldering grades

Most bouldering guidebooks opt for one clear grading system, but it’s worth mentioning the use of hybrid grades that could cause confusion. In particular, bouldering problems in the BMC gritstone Peak District guidebooks are given a V grade, as well as an English traditional technical grade. If you’re a traditional climber who boulders too, this can be helpful, especially in qualifying the difficulty of easier problems. But for most boulderers, I suggest you just ignore the trad technical grade – and note that it is not a Font grade, in spite of appearances.

However, what is more useful is when the Font or V grade is accompanied by a full trad grade (e.g., E2 5c) on high ball problems. Because bouldering grades do not take into account the height and risk of injury, to see a trad grade too will instantly tell you it’s a high enough problem to be classified as a micro-route. Which means you could still boulder it, but you either need enough pads and spotters to reduce the risk of injury from a fall, or treat it more like a solo … or get a rack, rope and harness and learn to trad climb!

News update: no longer a Burden!

To finish with a news update on the hardest bouldering grade. Spring 2023 has been a busy and exciting time in elite bouldering, with some of the strongest boulderers in the world racing to repeat Burden of Dreams. It is the first V17/f9a and arguably the most difficult of the handful that exist. It was first climbed by Nalle Hukkataival in 2016, having taken him three years and 4000+ attempts! Many have tried and failed to repeat the problem. Then along came Will Bosi, an unassuming bespectacled Scot, who managed to send it on April 12th 2023. Not only was it a phenomenal achievement, but it was interesting to witness his training methods, including the use of laser-scanned replica holds on a 40-degree indoor wall.

Well done Will – we look forward to your future successes … and perhaps the first V18!?

The post Bouldering Grades, Explained appeared first on Cool of the Wild.